On AI Art Discourse

First: I am fully convinced that our development of deep learning has outpaced our societal progress and we are absolutely not ready to deal with the consequences of unleashing deep-learning-capable consumer devices into as corporatist and click-driven a world as ours. Crunching corpora acquired without—and often against—consent or notice for gain—of any form, not exclusively monetary—is deeply problematic and unethical. If you expect this post to be a middle-ground take that accepts even part of the current state of imagery generated by models trained on unconsenting artists’ own work, stop reading now. Destroying someone’s right to own their own creative output is not justifiable.

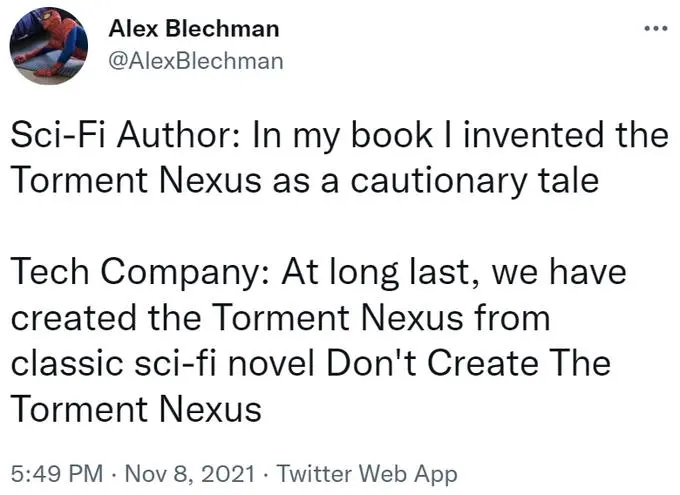

But there’s an argument I hear a lot online that’s deeply troubling to me, and it worries me greatly where we’ll end up if it does not get rejected entirely in the process of pushing back against exploitative AI.

Note that I hate the use of the term “AI” to only mean deep learning, so while when quoting others I’m not going to alter their words, I will, myself, use the term “neural network output”.

“AI Agents Are Not Artists”

This is a deeply unsettling and fundamentally flawed argument, but it shows up in online discussion with an extremely concerning frequency. Let’s first examine why it’s flawed.

First, the argument that “Neural networks cannot create art because it is incapable of creativity” is fully based on a false dichotomy. No AI nor other program exists in a vacuum, removed from human influence; they’re a product of human creativity. The ability of the program itself to be creative or think abstractly is entirely irrelevant; no more does a neural network need to be creative to be used to create art than a paintbrush or MIDI controller.

Systems like Midjourney use a human-provided (therefore necessarily including a degree of creativity and intent) prompt to derive images from an algorithm trained on a corpus of human-created (therefore necessarily including a degree of creativity and intent) imagery—therefore its output is necessarily a result of human creativity. Whether Midjourney itself is capable of creativity and artistic intent is of no importance; the program is the result of human creative work, it did not write itself—and if it did, that would only serve to prove it capable of creativity.

Second, the argument always draws an arbitrary line in the sand just beyond what the person making it is comfortable with. Anything up to that line is “real” art, usually because it predates the widespread availability of content-generating neural networks; anything beyond is “just an algorithm”.

Generative art far predates commercial neural networks and generally quickly reveals the deep-rooted problems with the “neural network output is not art” argument. A modular synth patch transforming electrical signals from mushrooms into experimental music is not the creative output of the mushrooms, but of the artist and musician. If the mushrooms are capable of artistic intent and creativity that may influence the end result, but the tools not being sapient in no way stop it from being art.

A program—whether a computer program expressed in code, an electronic one, expressed in circuitry, or even just a mental algorithm to follow—can be seen as a mapping of static input and dynamic input into an output :

The static input is the program itself; the dynamic input is provided to the program when it runs. A neural network can be viewed as a program that takes a training corpus as its dynamic input and produces another program—the trained model—which takes dynamic input as a prompt and produces an output:

The mushroom patch example above had its —the connections and settings for all the electronics—provided by a human, and takes its from a nonhuman source, yet produces artistic output. A trained model takes a human prompt (); how can its output, then, be less artistic than, at the very least, that of the mushrooms? Hell, a lot of generative music artists build patches that generate music without human input beyond the patch itself () at all, whether physically or entirely in software.

Third and least significant (for now), the argument relies on the actual incapacity of neural networks for intent or creativity. It has a form of movable goalposts built into it, because to foolishly accept it as valid is to take upon yourself the task of eventually having to solve the problem of measuring and recognizing consciousness, if our AI development ever reaches the point where that would become a question.

“AI Art Is Not Art”

Building machines that create art has probably been a dream of many artists and inventors for as long as we’ve had automation. As a musician and someone doing research in algorithmic storytelling, I’m most familiar with the history of algomusic and algo-literature; experiments in machine-generated literature date back centuries, and have employed computers as far back as the early 1970s, with Sheldon Klein et al’s 1973 Novel Writer and James R. Meehan’s 1977 Talespin immediately coming to mind as hallmark developments. David Cope’s Emily Howell, described in his 2005 Computer Models of Musical Creativity, is perhaps the best-known example of a computer program generating new music.

My own work, and my lifelong dream, is in procedural storytelling and narrative-generation for video games, a large chunk of which is also applicable to generative music—after all, a piece of music is itself a form of story. I dream of building a system which the player can collaborate with creatively in much the same way a TTRPG player works with their Game Master to build a story together, or how musicians play off each other at a jam session. I dream of a system which can be a satisfactory creative partner for its user.

It worries me greatly to hear the same crowd that previously fought for video games to be recognized as art now reject algorithmic outputs as “not art”, “not human enough”, “not creative”. Yes, as an artist I don’t want to be forced into a world where the decades I spent learning and practicing my art are rendered worthless and irrelevant by someone who unethically scraped millions of works off Artstation against their creators’ consent. I don’t want to be at risk of someone creating a “Fox’s music generator” in five minutes by retraining a model on my work and having it spit out a thousand albums.

But I also don’t want to wake up in a world where we reject this not because it is unethical and vile, but because someone deems it “not art enough”.

An Iron Wall

Vocaloid music doesn’t devalue human singers. Electronic music, programmed in a MIDI piano roll, does not devalue piano virtuosity. Generative art should not devalue human artists, but it will do so if we help it by creating a precedent of rejecting it as “not art”.

Push back against exploitation of artists, push back against building systems, without their consent, designed to strip their work of its uniqueness. The systematic erosion of artists’ rights perpetuated by training deep learning models on their creative work must be denounced and rejected.

I want it to be denounced and rejected in a way that stands up to scrutiny; I want it to be denounced and rejected completely and unambigously, with an immutable iron wall rather than arbitrary lines in the sand prone to being redrawn in either direction at will. Consent and the artists’ ownership of their work are immutable iron walls; subjective judgements of whether something is art or not based in the amount of effort or human control its creation entailed not only hurt artists, but leave future wiggle room for the “deep learning at all costs” crowd and corporations to redefine the boundaries of what is acceptable. This gate must not be left open.

Preserving our freedom and right to create without our work being used to train soulless corporatist AI models requires condemning algorithmic exploitation; but to not hurt artists, preserving that creative freedom also requires that it be rejected because it is exploitation, because it is unethical, because it erodes our rights—and not on the basis of how much effort a finished result requires or how creative it is. To protect creative freedoms and rights we must recognize both that anything can be art, and that unethical art must still be condemned; in being careful not to gatekeep art, we must assert instead that the quality of being “art” can never justify exploitation.

I’m scared about where the galloping adoption and deployment of deep learning will take us. In a world that seems happy to, every day, hand over its privacy and rights to megacorporations, deep learning—with its otherwise awesome potential for making lives better—seems like a nightmare machine, threatening to erode our rights entirely if given insufficient oversight for even a second. And right now it has extremely little of that oversight. It’s up to us—the users, the targets—to reject that future. It’s up to us to defend our own freedom to make art—even if it’s “just a program”.